"Don't pay attention to the critics - don't even ignore them"

— Samuel Goldwyn, penniless immigrant, producer of Hollywood's first major motion picture

"You cannot overtake 15 cars when it's sunny, but you can when it's raining."

— Ayrton Senna, greatest Formula One driver of all time

"Never go to sea with two chronometers; take one or three"

— Satoshi Nakamoto, comment in version 0.1 of the bitcoin code

"If I skip practice one day, I notice.

If I skip practice two days, my wife notices.

If I skip practices three days, the world notices."

— Vladimir Horowitz, greatest pianist of all time

"A wall has always been the best place to publish your work."

— Banksy

December 2024

Dear Fellow Investor,

Can a page have three sides? What if it has to?

Passing through the initial gates of the University of Chicago’s Ph.D. program in the 1990s required passing two brutally difficult exams, one after each of the first two years in the program. Called preliminary exams, or “prelims” for short, they were anything but, thoroughly testing knowledge of an entire field such as management, accounting, finance, or statistics. Fail either test and get kicked out of the program.

Entering the program straight from undergrad, amidst fellow students who already had Ph.D.s in engineering and physics, I found myself immensely underpowered in statistics. That was not ok. I decided to take nine statistics classes my first year, and none in any other field. Total immersion.

With regular classes ending late May and the “stat prelim” not until late August, I had to determine the optimal time to begin studying. Starting immediately was tempting. 12 weeks to prepare, enough time to go deep on everything. However, zero chance of retaining knowledge from material I reviewed those initial weeks of study on exam day – the time distance, multiplied by the material’s complexity, was just too great.

At the other extreme, I could cram the final two weeks. Everything I covered would be fresh in my mind on test day. However, zero chance to review all potential material over which I would be required to demonstrate mastery – just too much to know, in too short a time.

I picked six weeks prior to the exam to begin my preparation. Not too hot, not too cold.

For my first official act, I duct-taped an old t-shirt over the tiny TV in my tiny one-bedroom apartment. No distractions. I then began to methodically populate the only study aid I was permitted to bring in the exam room: a single 8 ½” by 11” piece of paper with, as I distinctly remember the professor-in-charge saying, “anything you want to write on both sides.” How do I summarize nine graduate level statistics classes on 187 square inches?

With my mechanical pencil my only social companion for those six weeks, I began writing formulas on my “cheat sheet” as tiny as possible, but just large enough to be legible. A single important chapter often took two full days to summarize and transcribe onto that increasingly sacred page. My delete button was my eraser – it was 1992 – and I had to continually re-assess the surface area of the remaining white space to ensure I could include the span of concepts to come, a perilous process.

One week before the test, I realized I did not have enough space for the critically important formulas and problems from my final three chapters on Bayesian probability. It was way too late to erase everything and start again, but if I did not include the missing material and it happened to be on the test, I would surely fail. I needed a third side of the page.

Desperate, and so cliché, I walked around the block to think. What could I do? After that first walk, perhaps embarrassing to admit now, I turned the page on its side to see if I could somehow fit the relevant material on to the paper’s 0.1mm edge. Jeez…

Towards the end of another walk, about to give up and simply hope the missing material was not on the test – my Ph.D. hanging in the balance – I figured it out. I screamed “Yes!!!” at the top of my lungs, then – fist pump, fist pump, fist pump – ran up to my apartment, and sat down at my desk. I picked up my yellow highlighter, and proceeded to write, in highlighter, the relevant material from those final three chapters. I could read the pencil under the highlighter, and I could read the highlighter over the pencil. I had found the third side of the page. I passed the exam.

THE LAW OF LARGE NUMBERS

At Stone Ridge, we build businesses based directly on material from that stat prelim, though I notice no correlation between exam question difficulty and business profitability. By far, the easiest topic on my 1992 exam – the Law of Large Numbers – made us, by far, the most money this year, driving about 85% of our ~$4B in firmwide trading profits.

In finance, the Law of Large Numbers is commonly misunderstood as “trees don’t grow to the sky,” or “Nvidia won’t grow 100%/year, else it will soon be worth $800 trillion, more than all the wealth in the world.” True, and nothing to do with the Law of Large Numbers.

The Law of Large Numbers is entirely, and only, concerned with how accurately we can estimate the mean of a sample distribution. Its central assumption – individual observations in a data set are independent of each other, which also means they are uncorrelated – allows us to conclude that, with enough observations, our mean estimate will be stunningly accurate.

Five years ago, outside of mortality data and casino gaming revenue, I had rarely seen the Law of Large Numbers operative in finance. In fact, we are taught “in a crisis, all correlations go to one,” so it is dangerous to even look.

What if that advice blinded us to powerful business models staring at us our entire careers? Decades later, could the easiest question on my stat prelim inspire us at Stone Ridge to reimagine traditional industries in new ways? Let’s consider the curious cases of the natural gas and casualty reinsurance markets.

“It is never too late, or in my case too early, to be whoever you want to be.”

— Benjamin Button, The Curious Case of Benjamin Button

In natural gas markets, the jargon PDPs (Proved, Developed, Producing) refers to land previously Proved to have gas underneath, now with wells Developed, and steadily Producing gas every day. PDPs are the least risky part of an energy company, but act as an anchor on their overall company P/B (price-to-book) ratio.

A declining asset, natural gas wells deplete continually over 20+ years until there is no gas left. Think of a PDP portfolio akin to a large, third-party asset management fund sitting inside a high-growth energy company, quietly off to the side, continually leaking AUM. Stand-alone PDPs, like any fund, would “trade” at P/B ~1, while leading US energy companies aspire to P/Bs of 2, or more. The market, appropriately, pays for exploration, and growth, not run-off.

At Stone Ridge, when it comes to expertise, we never pretend we have it when we do not, but we are equally unafraid of its absence. Not historically energy investors, about five years ago we had a hunch about PDPs and visited dozens of drilling sites – in hard hats and work boots – to learn more. Our hundreds of questions – ranging from kindergarten to Ph.D.-level difficulty – were kindly answered by a brilliant faculty of energy practitioners, forming a proprietary textbook we studied intensely and without distraction. Total immersion. We then made a series of observations, each building on the one prior, carefully wrote them on our “cheat sheet”, and sat for the energy exam.

University of Chicago Stone Ridge Energy Prelim: Consider the following non-traditional perspective.

Some energy companies are considering selling PDPs to Stone Ridge. The more PDPs energy companies sell, the lighter their PDP-driven P/B anchors. The more PDPs Stone Ridge buys, the higher the ROEs of its (re)insurance company investors, and the less their end clients pay for insurance.

Do you agree or disagree? Show your work. Bonus: use the Law of Large Numbers in your answer.

Stone Ridge answer:

First, engineers can accurately, but not perfectly, predict the total volume of gas that will come out of a given well over its life.

Second, the prediction error for any given well in a basin is uncorrelated to the prediction error for any other well in that same basin – this is true, on average, both at every point in time, and over time. The Law of Large Numbers works (almost) perfectly to forecast total gas volume production during, and through, the life of a portfolio of wells. The earth did not have to be that way, but it is. This observation – that volatility of production volume is virtually eliminated by owning enough wells – has profound investing implications. Low volatility of production volume, however, is a necessary, but not sufficient, condition for low volatility of returns. We still have to sell the gas.

Third, Stone Ridge can marginlessly hedge price risk out 7-9 years. This turns a 60-vol asset – spot natural gas – into a strikingly low-vol hedged stream of cash flows.i

Fourth, we can securitize those low-volatility cash flows, rate the vast majority of the capital structure investment grade (IG), and deliver 200-250 basis points (bps) of yield over comparably rated corporate credit. And we can make it all arrive with minimal left tail risk because the security has reliably zero correlation to…everything. At Stone Ridge, we like businesses with returns dependent on geological processes under the Earth, and the Law of Large Numbers, not the whims of central bankers.

Fifth, our IG security can be extraordinarily attractive to (re)insurance company balance sheets, including our own reinsurer, which means we can do very (very, very) large deals, which are especially strategic to the largest energy companies. A “Super Major” would much rather sell $3B of PDPs, all at once, to Stone Ridge, than attempt ten individually negotiated $300M deals, over several years, each with execution uncertainty throughout a typically full year negotiation and closing process. Size is a service. Thus, 200-250 bps over.

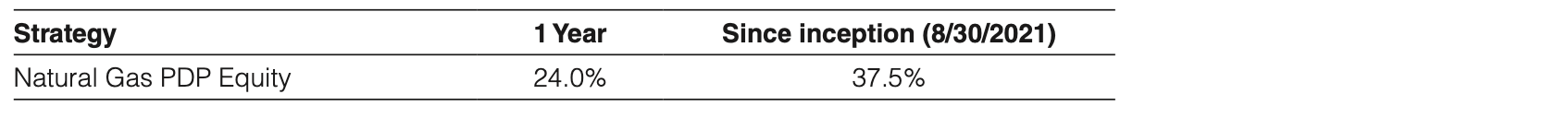

Final answer: Agree. Stone Ridge vehicles acquired ~$6B of natural gas PDPs over the last three years. I expect closing $5-10B more in 2025. We internally source, structure, execute, and risk manage our acquisitions, with no information, or fee, leakage to bankers. The ~$2.1B IG tranches of our last deal priced at 240 bps over comparably rated corporate credit and was purchased by 15 of the bluest-chip (re)insurance companies in our incredible country. That security was oversubscribed by more than the total size of almost every previous IG issuance in the history of the industry.ii The equity tranches – with Stone Ridge owners/employees, as cornerstone investors, bearing the first loss risk – have returned net over 25%/year, with no correlation to traditional markets.iii

Extra credit: Since the Stone Ridge energy business began, Stone Ridge insurance company partners – the highest rated in the industry, and among the most iconic firms in our country – have produced record sales in their whole life and income annuity-related products. This shift is not entirely, or even primarily, due to Stone Ridge, but our suite of superior fixed income replacement products has had an impact, we are proud to have played a small part, and our impact will be increasingly significant in 2025 and beyond. The benefits of higher investment income get passed on to policyholders in the form of more insurance for less money, a larger annual dividend, and a larger surplus, which helps make already super-super-safe firms even safer. At Stone Ridge, we run to work to help all Americans, including our own families, get more, and more reliable, life, property, and casualty insurance for less money.

Grade: Pass.

Whew. Ok, so far, so good, but remember the Ph.D. requires two prelims.

To prepare for the next one on casualty reinsurance, the professor-in-charge told us to review Adam Smith’s theory of banking, King Arthur’s quest, and Rocky Balboa’s primary conclusion. He was kind enough to give us a heads-up that technical knowledge of Combined Ratios, and their link to effective internal company interest rates, will be on the test. This time, the prelim was a take-home, and it came with some recommended reading.

University of Chicago Stone Ridge Casualty Reinsurance Prelim: Consider the following non-traditional perspective.

Virtually everyone believes modern banking works, yet Stone Ridge strongly disagrees, arguing the “dead pledge” is banking’s fatal flaw and that reinsurance can provide a better solution.

Do you agree or disagree with this perspective? Show your work. Bonus: use the Law of Large Numbers in your answer. Recommended reading below.

“Bank credit is always suspended on the Daedelian wings of paper money.”

— Adam Smith, An Inquiry Into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations (1776)

Amidst genius philosophical insights in Smith’s Wealth of Nations, his foundational “real bills doctrine” was perhaps the most practically prescient, and most tragically ignored.iv

In Smith’s time, individual bank customers temporarily “deposited” gold and silver, which could be withdrawn on demand. Due to their reliance on overnight funding, Smith warned that banks should not support long-term loans. In contrast, Smith argued that “real bills” – short-term loans to commercial traders, backed by salable physical merchandise – were safe. Before an unexpected bank run could cause insolvency, collateral could easily be sold.

Not quite proposing a narrow bank, but rhyming, Smith was the first to argue that a bank can only prudently lend to a borrower the amount that the borrower keeps in liquid reserves at the bank. Post-Wealth of Nations, and driven by Smith’s “real bills doctrine,” banking was essentially defined by its avoidance of long-term loans.

The father of capitalism singled out mortgages – “dead pledge” in French – for banking opprobrium. In the strongest possible terms, Smith advised that mortgages be made only by wealthy individuals, whose personal balance sheets – unlike banks – were well-suited to holding illiquid assets for decades.

Smith, however, only gets an A- for not also considering insurance-related business models. Lloyd’s of London had been active for almost a century before Smith published Wealth of Nations. Smith argued for a higher grade, unsuccessfully, citing the fact that Lloyd’s primarily served coffee, with milk, sugar, and insurance merely optional add-ins, during 89% of its first post-launch century.

Tragically, Smith’s real bills doctrine, and his mortgage advice, were soon discarded into the trash bin of history. Generation after generation of alchemists bankers, instead, have never stopped trying to make lead gold land liquid. It is not. Maturity mismatch – borrowing short, lending long – and not permanent credit losses, caused, and still cause, virtually all bank failures. Despite “unlimited” government-backing and central bankers willing to “do whatever it takes,” the Holy Grail remains at large, and no one can predict when demand depositors will demand their deposits returned.

All fractional reserve banks have the same flawed, alchemy-dependent business model: borrow short, lend long, rub the Philosopher’s Stone on mortgages to make lead gold land liquid, hope the inevitable bank run does not occur on your watch, lobby for a post-run bailout if it does, and try to get rich earn a spread in the interim. Rinse, wash, repeat. Maximizing moral hazard and minimizing morality, thuggishly redistributive bank bailouts almost always come, sadly.

Stone Ridge answer: Daedelian wings are no way to fly.

“Ain’t gonna be no rematch bailout. Ain’t gonna be no rematch bailout.”

— Apollo Creed, Rocky (final scene), assuming Rocky wanted a rematch bailout

“Don’t want one."

— Rocky, Rocky (final scene)

At Stone Ridge, we always wanted to build the opposite of a bank: borrow long, lend short, try honestly to earn a spread. No maturity mismatch, no such thing as a bank run, no possible bailout.

Don’t want one.

“Banks must be trusted to hold our money…but they lend it out in waves of credit bubbles with barely a fraction in reserve”

— Adam Smith, An Inquiry Into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations (1776) Satoshi Nakamoto, BitcoinTalk (2010)

To see if we can build a better bank, and perhaps help stabilize the financial system in the process, consider the following series of observations, each building on the one prior.

First, reinsurers “borrow”, bank-like, by taking in premium from their insurance company clients (akin to depositors) in exchange for risk transfer services. For any given underwriting year, if a reinsurer accumulates claims (i.e., accepts transfers of loss from insurers) equal in size to how much it earned in premium that year – in industry jargon, a “Combined Ratio” of 100, including all business expenses – that reinsurer essentially financed its asset strategy at a zero cost of funds. A 0% borrowing rate is not bad, especially since reinsurers can be levered 3x or more.

Key insight: reinsurers take in premiums (i.e., cash from insurance companies, sometimes called “float”) before they have to pay the associated claims – often by many years.

Second, even the very best individual insurers, with world-class underwriting organizations, have a cost of funds (i.e., the “interest rate” at which they essentially “borrow” from their clients) that can fluctuate wildly year-to-year depending on the claims they receive, with annual variation occasionally 20% or more. In addition, in any given year, looking across insurers, we typically observe borrowing rates varying by 20-40%, depending on their range of business lines. That’s a lot.

Third, reinsurers, by pooling disparate risks from dozens or hundreds of insurers, experience far lower, but still quite high, variation in their own effective borrowing costs. The “interest rate” (i.e., the Combined Ratio minus 100) of individual reinsurers, even with world-class underwriting organizations, can vary year-to-year by 10% or more, and by 10-30% or more in any given year looking across reinsurers. That’s still a lot.

Fourth, even the most globally diversified casualty reinsurers, while sharing similarities, are also in many fundamentally different – and unrelated – lines of business. One might reinsure medical malpractice in Australia, another commercial auto in the UK, another D&O in Korea, and yet another workers compensation in the US. Each reinsurer, in each of those business lines, may have a world-class Combined Ratio of 100 as a long-term average. However, because their business lines are sufficiently unrelated, their “prediction errors” – that is, the deviations of their Combined Ratios around 100 – are cross-sectionally uncorrelated in any, and every, given year.

Aha! The Law of Large Numbers strikes again.

Taken together, these observations led to two fundamental insights, which ultimately caused Stone Ridge to launch a casualty reinsurer of reinsurers (not a reinsurer of insurers), Longtail Re. And typical of Stone Ridge, in Longtail Re we share risk with many of the same world-class reinsurers from our industry-leading catastrophe reinsurance asset management franchise.

Fundamental Insight #1: combining positively selected, aligned, and hyper-diversified liabilities of multiple casualty reinsurers into a single entity could deliver industry-changing improvement in the level and variability of float expense (i.e., minimal variability in the “interest rate” at which Longtail Re “borrows”).

Fundamental Insight #2: access to superior short-duration fixed income replacement strategies that reliably outperform traditional long-duration fixed income strategies and distribute high monthly cash flows to pay ongoing claims – strategies Stone Ridge was already proprietarily producing at scale (see, for example, PDPs above) – could deliver industry-leading book value growth.

Final answer: Agree. In its first five years of life, Longtail Re’s all-in “borrowing costs” have fluctuated in an industry-leading range of -1% to -3% – not a lot – while our return-on-assets (ROA) has annualized at an industry leading 6.3%, ~3x the average of the top three global reinsurers (it has been a particularly challenging period for traditional fixed income strategies).v Combining our two fundamental insights, Longtail Re’s 20% annualized ROE has been 4x the average of the top three global reinsurers.vi

I expect Longtail Re to end 2025 with ~$4B of assets, and continue its responsible growth trajectory from there, provided the market stays attractive. It certainly is right now.

Like everything we do at Stone Ridge, in casualty reinsurance we have skin in the game. Stone Ridge owners/employees own more than 40% of Longtail Re and have more than $1B invested in our various reinsurance strategies.

Extra credit: $1M invested in Microsoft 25 years ago would be worth ~$12M today. Not bad. That same investment made in Hannover Re instead – an inspirational partner to Stone Ridge whose culture, and results, we deeply respect and admire – would be worth ~$25M. Perhaps working to build the best performing reinsurer in the world over the next 25 years will be just as interesting?

Grade: Pass

Whew, again. We get to stay in the program and prepare for our dissertation.

During our first post-prelim year, our dissertation chairman guided us to read widely, yet somehow coherently, on the architecture of asset management business models, the proper role of critics, longitude, and rent control.

OVERTAKING 15 CARS WHEN IT’S RAINING

There are roughly two business models of underwriting, or asset origination. Underwrite yourself (own asset originators) or underwrite the underwriters (partner with asset originators). At Stone Ridge, we have followed the latter since firm inception and passed on dozens of individual opportunities to do the former.

Our approach is to partner, not compete, with the best underwriters in the world. With deliberate practice, high cadence connectivity, and internal private scorecards that matter deeply to us, we seek to earn and re-earn the right to be the most strategic, long-term risk sharing partner to each of our cherished underwriting partners. Why is this business model answer so obvious to us, at least for us?

The Wisdom of Wise Crowds

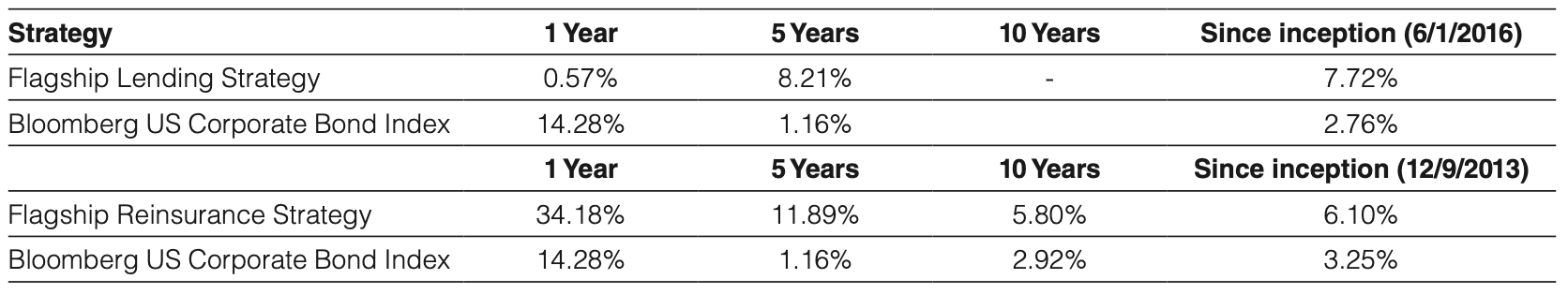

Our alternative lending franchise has purchased ~9M of individual loans worth ~$40B, in partnership with the leading personal and small business origination platforms in the US. We, uniquely, see the historical results of all partner platforms, across all loan grades, borrower types, origination channels, and products (including experimental initiatives for which we are often the only capital). This valuable proprietary data guides our active management – that is, our active underwriting – of the underwriting of our partners. Our flagship lending strategy has outperformed traditional fixed income by 5%/year since inception in 2016, and every loan we make allows creditworthy Americans to bet on themselves, propelling our country forward.

Our catastrophe reinsurance franchise, our first, has purchased ~$9B of cat bonds and supported ~$110B of cat limit via quota shares, in partnership with the leading global reinsurers. We, uniquely, see the historical results of all partner reinsurers, across all perils, geographies, attachment points, and business lines (including experimental initiatives for which we are often the only capital). This valuable proprietary data guides our active management – that is, our active underwriting – of the underwriting of our partners. While we don’t call it a comeback, our flagship fund has cumulatively returned net 92% the last two years (and, yes, it has been here for years). When we lose money, which we do at scale from time to time, we stand behind people as they rebuild their homes in their darkest hour.

Our single-family rental (SFR) franchise has exposure to ~60K homes, in partnership with the leading independent operating platforms in the US. We, uniquely, see the historical results of all partner operating platforms, across cities, neighborhoods, price points, and home ages. This valuable proprietary data guides our active management – that is, our underwriting – of the underwriting of our partners. Since franchise inception four years ago, the Case-Shiller index outperformed the broad US real estate benchmark by ~6%/year, and we have outperformed Case-Shiller by ~5%/year. Partnering solely with maturity-matched “forever balance sheets” in explicit rejection of banker’s mythological quest for liquid land, we have set out to do nothing less than make American housing affordable again.vii

These business model architectures rhyme with those of our volatility risk transfer, post-war & contemporary art, longevity income, and drug royalty franchises. Across Stone Ridge, we currently have 35 underwriting partnerships, each a cherished and genuine relationship. This means that we kindly, but directly, share the good and the bad along the way, and work on problems – our partner’s or ours – as they arise, together.

Unlike asset managers who own originators, we have no obligation – legal or social – to continue working with any given underwriter. We can stop on a dime. However, while making necessary line-up changes from time to time keeps everyone sharp, we have never, and will never, make changes just to make them. Instead, we follow the wisdom of our wise crowd, and always seek to race in the rain.

DON’T PAY ATTENTION TO THE CRITICS. DON’T EVEN IGNORE THEM.

Immediately after WWII, primitive tribes in Fiji first used machetes and brooms to create long flat strips in open fields. They then built large wooden bird idols and erected tall wooden towers for climbing. They reasoned that if they recreated the structures – runways, airplanes, control towers – that, during the war, occasionally resulted in stray food – cargo – accidentally falling out of the back of airplanes into their territory, perhaps those planes would return and drop cargo again.

Anthropologists coined the term “cargo cult” to mean effort designed to create a specific outcome that has no relationship to the output of the effort.

Fiat central bankers observe that wealthy people have money, so they reason that printing more money will make more people wealthy. Printing pieces of paper to attract prosperity is no less preposterous than building a wooden bird to attract an airplane.

Printing paper money is like a stock split. Nothing changes about the quality of a company’s products or its client relationships when the price halves and the share count doubles overnight via split. Just as one share of post-split stock represents less of a claim on the company than it did the day prior, immediately after a fresh fiat counterfeiting printing, one unit of paper money represents less of a claim on goods in the economy than it did the day prior.

Since 2017, bitcoin has been Stone Ridge’s treasury reserve asset – we cash sweep our fiat profits into bitcoin – because I know the difference between a wooden bird and a military airplane.

Fiat central bankers, cargo cultists, can print money. They cannot print anything money buys.

Ethically, at an individual level – as a function of physics at a societal level – we must produce before we can consume. We bitcoiners, emerged from our rabbit holes, have total clarity on the direction of causality.

“It isn’t obvious the world had to work this way. Somehow, the universe smiles on encryption.”

— Julian Assange, cypherpunk and OG bitcoiner

No one forces anyone to use bitcoin, nor does anyone need anyone else’s permission. The power in incomprehensibly large numbers makes bitcoin work. For the same reason, bitcoin favors the individual. Normally the men with the biggest sticks make the rules, but no army in the world can break strong cryptography.

Beautiful and silent, the bitcoin network sits blanket-like atop the earth’s topography, robust in its unstructured simplicity. Anyone can transfer bitcoin to anyone, anywhere, erasing borders and linking humanity. On a video call, hold up a barcode. On a message app, click one button. Or just whisper 12 words.

Or don’t whisper. Take those 12 words privately rattling around in your head and walk across a border. They may contain $1B of bitcoin, but forget them, and lose your bitcoin.

Peaceful and provably resistant to coercion, why does bitcoin generate such intense animosity?

Perhaps for the very reason that it is voluntary? Or perhaps because its foundational promise – individual sovereignty at the expense of personal responsibility – is offensive to the foundational world view of those confused critics who think they’re in charge.

World Economic Forum (WEF)

December 15, 2017 (499497, 1 BTC = $17,707): “The electricity used in a single bitcoin transaction could power a house for a month…bitcoin mining’s energy use is growing 25% per month…bitcoin will consume as much energy as the US in 2019…by 2020, bitcoin mining could be consuming the same amount of energy as the entire world.”

All WEF sentences above are false. And as of 2024, bitcoin accounts for less than 0.2% of global energy, not 100%. The WEF also gets the impact of bitcoin mining on human flourishing backwards. The world has never had a profitable use of energy that is location independent. Now it does – bitcoin mining – and the long-term implications are world changing.

Think about miners utilizing end-of-life, stranded, and otherwise useless, PDPs, or capturing flared methane to unleash domestic oil production, or re-directing garbage-landfill methane to improve neighborhood residential health, or activating non-active peaker-plants, or (much, much) more. The list, and staggering scale, of un-, or under-, utilized energy sources for bitcoin mining – each of which directly reduces production expenses for energy companies, and in many cases uniquely makes otherwise polluted air clean – is limited solely by our imagination.

Bitcoin mining – by directly causing sustainably non-subsidized, almost incomprehensibly enormous development of abundant, cheap energy – will directly lower the energy bills of tens of millions of Americans living in energy poverty, and be the sole reason hundreds of millions of humans in Africa experience electricity for the first time.

In the decades ahead, watch out for the ubiquitous headline “Mining bitcoin is wasting energy” to be replaced with “Not mining bitcoin is wasting energy.”viii I can’t wait.

European Central Bank (ECB)

November 30, 2022 (765357, 1 BTC = $16,445): “The current stabilization of bitcoin’s value…is an artificially induced last gasp before the road to irrelevance…bitcoin is not suitable as an investment…bitcoin should not be legitimatized.”

February 22, 2024 (831584, 1 BTC = $51,282): “The fair value of bitcoin is still zero.”

October 12, 2024 (865737, 1 BTC = $63,196): “Non-holders should…oppose bitcoin…advocate for legislation to prevent bitcoin prices from rising or to see bitcoin disappear altogether.”

Two months ago, King Canute the ECB impotently commanded the tides bitcoin to stop rising. Bitcoin does not, and cannot, rise. Bitcoin ticks. Self-imprisoned in their cargo cult cage, the ECB does not yet think in bitcoin. Alas, the ECB’s final missive above was an intentional and duplicitous distraction. In the ensuing nine weeks, they plunged the Euro into a culture-rattling 45% shock devaluation. Even Egypt had the common courtesy to limit its latest EGP devaluation to only 34%.

When the ECB promised to “do whatever it takes” to destroy save the Euro, it marked a dramatic acceleration in their production of wooden birds. At the time, one bitcoin could be exchanged for the best croissant in Paris. Today, that same one bitcoin rents a stunning four-bedroom apartment on the Champs-Élysées for a year. During your stay, the owner will throw in an unlimited croissant supply. I highly recommend Paris, on bitcoin.

Vatican

March 8, 1633 (376 B.S.): “Galileo vehemently suspected of heresy…must not believe the Earth moves…contrary to Holy Scripture…advocate for legislation to prevent heliocentrism and to burn Galileo at the stake.”

Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC)

After more than a decade of extralegal delay, and only after losing in court this January, the SEC was forced to approve a bitcoin ETF. Post the court loss, the voting process of the five Commissioners should have been a 5-0 formality. Instead, one Commissioner threw her toys out of the crib still voted “No.” In composing her dissent, the Commissioner used ChatGPT in “hysterical anti-bitcoin teenager” mode.

January 10, 2024 (825187,1 BTC = $42,582): “Bitcoin is subject to manipulation…51% of bitcoin trading volume is bogus…bitcoin spot markets are Petri dishes of fraudulent conduct with no systematic oversight…bitcoin is unfit for investors…criminals use bitcoin…bitcoin funds weapons programs to aid attacks on civilians…bitcoin has historically been subject to volatility…I AM CONCERNED THERE WILL BE CONFUSION.”

These are not the writings of serious people. Unhinged leaders, and their bitcoin derangement syndrome (BDS), destroy the credibility of their organizations. Completely gone at the WEF and ECB, the reputation of the SEC lies in tatters due to about-to-be-gone Commissioner Confused above, but especially because the also-about-to-be-gone Chairman, Captain Dishonor, discharged the Oath he took on April 17, 2021, to “support and defend the Constitution of the United States” with criminally abject, but ultimately impotent, disgrace.

“If you see fraud and do not say fraud, you are a fraud,” once wrote a very wise man.ix

In mid-2023, Captain Dishonor decided he alone knew better than all the American people. Worse, he abused his position to direct the State’s monopoly on violence to override the collective talents of, and hard-fought liberty the Constitution enshrines in, the ~335 million of us. In an apex of arrogance, he testified, “we don’t need more bitcoin.” His tragic comments – textbook bitcoin derangement syndrome (BDS) – devastated the most vulnerable Americans as the US dollar crashed 82% in the ensuing 18 months. Had it not been for Captain Dishonor, those most vulnerable Americans – entirely without access to valuable hard assets such as art or real estate – would have had cheap and easy access to shift their savings, however meager to start, to bitcoin. They would have been able to preserve the value of their hard-earned labor, rather than see it predictably eviscerated. For shame, Captain Dishonor, for shame.

In last year’s version of this letter, I wrote:

“The propulsive tentacles of the SEC Chairman’s extralegal agenda…have ceaselessly sought expansion beyond legitimate boundaries. In the words of a heroic fellow Commissioner (“Commissioner Heroic”), his agenda reflects ‘a loss of faith that investors can think for themselves.’ We can.

In the past year, the Courts have repeatedly defeated the Chairman’s agenda. More SEC defeats are likely. All will be ok.”

In this regard, all was, and is, indeed ok. In 2024, Captain Dishonor lost, again – in court – every single one of his one-is-too-many additional extralegal attempts to inappropriately thrust his personal tentacles into the private lives of free Americans. Then he finally lost his job.

I no longer care enough about the WEF and ECB to even ignore them. I care a lot about the SEC.

Fortunately, help is on the way. Faster than a speeding bullet, the awesome new SEC Chairman’s Wonder Twins power will (re)activate next year with aforementioned Commissioner Heroic. For years, at times singlehandedly, Ms. Heroic shielded the greatest securities market in the world against repeated attempts at regulation without representation from Captain Dishonor.

Commissioner Heroic’s Baby on Board, Hitchhiker’s Guide, Scarlet Letters – among the most powerful, inspirational, and important US political speeches this century – remind us of the unique exceptionalism of our country, the priceless value of our governing document, and bear witness to the potency of non-violent bravery. America has been lucky to have her on our wall. We get her for six more months. Thank you for your service, Commissioner Heroic. You will be missed and not forgotten.

A KNOCK-KNOCK JOKE, A RIDDLE, AND A SONG LYRIC WALK INTO A BITCOIN BAR

Money is valued not for its own sake, but solely for its prospective exchange utility. That’s a fancy way of saying we hope it keeps its value long enough for us to trade it in the future for something we actually want. Nobody wants green little pieces of paper. Or bitcoin. We want what those things can buy us in future. Perhaps an education, a dream house, a wedding, a bucket-list trip.

Those who excel at delaying gratification, and mentally managing the associated uncertainty along the way, end up accumulating the vast majority of capital and enjoying the vast majority of health and prosperity. Low time preference is the most reliable source of life inequality. This means stay humble, stack sats, and HODL an uncomfortable amount of bitcoin for an uncomfortably long time. Bitcoin is the most potent device ever invented for transferring wealth from the impatient to the patient. Be patient.

Knock knock

Who’s there?

HODL

HODL who?

Nobody HODLs

While HODLing bitcoin is necessary, and entirely sufficient, savings advice, our knock-knock wisdom teaches us that nobody, in fact, HODLs. Every “never sell your bitcoin”-HODLer will sell their bitcoin. Some of it, at some point. This is the entire point of having money in the first place. To be clear, this absolutely is not investment life advice. Your personal version of time is finite. Take the trip. With bitcoin, you just get to take a better one.

What has cash flows, but doesn’t?

Every investment has an expected cash flow. In some cases, the issuer decides the timing. At least $100 trillion of global wealth falls into this category. Examples include stocks and bonds. We can generally check their prices regularly, and those prices change in reaction to new information.

In other cases, the asset owner decides the timing – that is, when they sell. At least $100 trillion of global wealth falls into this category, too. Examples include art, gold, and owner-occupied homes – and bitcoin, the answer to our riddle above. Asset prices also regularly change in reaction to new information. Some folks Zillow-check the price of their house more often than some bitcoiners check the price of bitcoin.

In the two paragraphs above, I see more similarities than differences. In challenging matters of valuation, however, I often find Jay-Z’s lyrical advice dispositive:

If you’re having valuation problems, I feel bad for you, son

I got 100 trillion problems, but cash flow ain’t one

— Jay-Z, 99 Problems, on the (non)importance of the distinction between issuer vs. asset owner-controlled cash flows in valuation theory

While there may be good reasons for someone to not yet own bitcoin, the common objections “but it does not have any cash flows” and used-pejoratively-but-axiomatic “but its price is only what someone else will pay for it” are intellectually lazy ones. Perhaps all it will take is a knock-knock joke, a riddle, and Jay-Z’s wisdom to tweak your no-coiner friend’s perspective and help them get off zero.

Now that we know bitcoin can generate cash flow upon a sale, how about using bitcoin to generate cash flow upon a non-sale?

Perhaps just in time to help HODLers HODL longer, look out for efficient (aka “cheap”) bitcoin-collateralized fiat lending – HODL loans – a powerful new weapon for every HODLer’s arsenal. Bitcoin is about as risky as a typical US stock – with realized volatility and maximum one-day drawdown statistics over the last five years ranging from about the 40th to 80th percentile of the largest 3000 stocks – and traded 24/7. That means bitcoin-backed loans are realistically less, and certainly no more, risky than a plain vanilla, Reg T, US stock margin loan. Those loans price at S + ~50 to ~150. Not-riskier HODL loans price at S + ~450 to ~950. Expect competitive forces to drive HODL loan pricing into the Reg T margin loan neighborhood in the coming years.

Remember, at Stone Ridge the first rule of product design is we build products we want ourselves. We still must pay our bills in fiat, and we too, grudgingly but gratefully, pay way too much, risk-adjusted, for our bitcoin-backed loans.

An efficient bitcoin-backed fiat lending market would increase the utility of our stack, keep bitcoin off the market, accelerate fiat debasement, which further increases the utility of our stack, which keeps bitcoin off the market, which accelerates…rinse, wash, repeat. Our bitcoin subsidiary NYDIG is preparing to enable all HODLers, including Stone Ridge, to unsheathe their weapon – borrowed fiat at a low rate – in an amount, and at a time, that is right for them.

NYDIG has facilitated billions of dollars of bitcoin-backed fiat loans, though none financed with float. Longtail Re has invested billions of dollars of float in asset-backed loans, though none backed by bitcoin. Imagine float-powered HODLing. We found the third side of another page. Stay tuned.

In the interim, however, it gives me great pleasure to announce Adam Smith as the exclusive spokesman for

NYDIG’s new HODL loan initiative. I am especially excited about this because of Smith’s stellar reputation for only promoting products he believes in and uses himself. Smith approached us, via email, leading with the observation, “Bitcoin is digital property. We finally have liquid land.” He’s right, of course. And remember, now he knows about insurance.

GOING TO SEA WITH AN ORCHESTRA OF CHRONOMETERS

A transaction involving a bearer instrument, such as a $100 bill, does not need to be timestamped. That is, we do not need to record the time of the transaction. If I give you a $100 bill, you have it, and I no longer have it. Physics, not trusted ledgers, takes care of telling us who owns what, and when.

A transaction involving an electronic instrument, such as a $100 wire transfer, does need to be timestamped. If I wire $100 to you, someone must verify that you have it, and that I no longer have it. We must also trust that person – or that bank or that government – to maintain the verification, via a trusted ledger. “The history of fiat currencies is full of breaches of that trust,” once wrote a very wise man.x

How can we transact electronically, but without (centralized) trust? That problem had doomed all attempts at electronic cash prior to Satoshi’s breakthrough.

I suspect, though I have no idea, that Satoshi was inspired by 1700’s clockmaker John Harrison’s version of the third side of the page, in figuring out his own, though the stakes were not getting through grad school. Harrison was motivated to save the lives of sailors. Satoshi wanted better money for the world.

“Since time keeps its own tempo, like a heartbeat or a tide, timepieces don’t really keep time. They just keep up with it, if they’re able.”

— Dava Sobel, Longitude: The Story of a Lone Genius Who Solved the Greatest Scientific Problem of His Time (1995)

Until the late-1700’s, ships regularly got lost at sea. Determining latitude was easy using basic instruments and the position of the sun and stars. Longitude had been impossible. Hundreds of ships, filled with brave captains and sailors, lost track of their east-west position, missed supply points, ran out of rations, and eventually drifted onto shore, with their long-dead crews aboard. Gruesome.

In 1707, four state-of-the-art British Warships with 2,000 soon-to-die military sailors lost track of their longitude soon after they left London and crashed at night. The British government, desperate, passed the Longitude Act, offering an enormous cash prize (equivalent to >$25M today) to anyone who could solve the problem of longitude at sea. Failing ideas involved the use of compasses, cannons, and wounded dogs. The ideas of gravity-famous Isaac Newton and comet-famous Edmond Halley, icons even at the time and the prohibitive early favorites on Polymarket to win the prize, failed too.

Harrison’s third side of the page, a special clock, was a groundbreaking practical solution to what modern computer scientists, 300 years later, would recognize as the Oracle problem.

Computers do not, and cannot, know anything about the outside world, and certainly nothing permanently reliable. The outside data source can be wrong, or the link to it can break. That’s the Oracle problem.

A 1700’s ship did not, and could not, know anything reliable about the outside world. Certainly not about longitude. Harrison’s third side of the page solution was a different way to measure time. He built a timekeeping device – the first ever chronometer – accurate enough to withstand ceaseless ship movement, which allowed sailors to know the time at their home port, and – for the first time ever – determine their longitude, saving countless lives.

How?

A clockmaker, Harrison had time on his mind. He knew that it took 24 hours for the earth to revolve 360 degrees, so one hour meant 15 degrees. He also knew that whenever the sun was overhead, sailors could conclude it was about noon local time.

If the sailors knew it was noon, and their Harrison chronometer read 2pm, the ship was 30 degrees (2 hours (i.e., 2pm minus 12pm) x 15 degrees per hour) away from home. With Harrison’s chronometer aboard, and long capable of calculating latitude, sailors could now also calculate their longitude and know their close-to-exact location. They stopped missing their supply points, stopped running out of rations, and the concept of “lost at sea” became largely a historical footnote. Harrison won the Longitude Act prize.

“If you don’t believe it or don’t get it, I don’t have the time to try to convince you, sorry.”

— Satoshi Nakomoto, BitcoinTalk (2010)

Between 1971 and 2009 – bookended by a US President de-pegging the dollar from gold and a UK Chancellor on the brink of his second bailout for banks – more than 50 hyperinflations devastated the lives of billions of people, none occurring in an economy with a commodity-based monetary standard. During that 38-year period, determining who owned how much electronic fiat was technically easy with trusted, central bank ledgers. Tragically, the history of fiat currencies was full of central bank breaches of that trust. A trustless, decentralized ledger, powering trustless, decentralized money, had been impossible.

Just as a stock certificate is title to company property, money is title to human time. People sacrifice their time for money, expecting to trade that money in the future for the time sacrifices of others. When central(ized) banks breach trust by printing money – destroying the savings, and dignity, of the innocently trusting billions of people who had not exchanged their savings for a valuable hard asset – they steal time. Gruesome.

Satoshi’s third side of the page, a special clock, was a groundbreaking practical solution to the Oracle problem, that computers do not, and cannot, reliably know anything about the outside world, including time.xi

No 2009 computer could trustlessly determine who owned how much electronic money, and certainly not in coordination with an arbitrarily large set of other, potentially adversarial, computers – including and especially central bank computers – anywhere in the world. Satoshi’s third side of the page solution was a different way to measure time. He built the first ever timekeeping device – initially naming it a timechain, only later renaming it a blockchain – accurate enough to withstand ceaseless central bank attempts at breaching trust, quietly and peacefully allowing any global citizen, anywhere, to opt-out of involuntary wealth and, worse, involuntary time, confiscation.

How?

A cypherpunk, Satoshi had time on his mind. Out of eight total references in the original bitcoin whitepaper, three were about timestamping. Satoshi’s sui generis genius: realizing that trustless timestamping required causality, unpredictability, and coordination, and inventing the coordination part.

Satoshi’s use of a powerful, one-way cryptographic hash function – you cannot unscramble an egg or rewind a SHA256 signature – provides the causality. Without causality – make event B impossible without event A first, make event C impossible without event B first – a central bank protocol could go straight to C, stealing time.

Satoshi’s use of proof-of-work – you must do work to guess the input that hashes to the provably-unknowable-in-advance required output – provides the unpredictability. Without unpredictability – trust physics and mathematics, not politicians, that guessing the correct input had no shortcut – a central bank protocol could go straight to C, stealing time.

Satoshi’s invention of the difficulty adjustment – the conductor of the bitcoin orchestra keeps the Law of Large Numbers-driven metronomic tempo at C=~10-minute blocks by ensuring that too many (few) accurate guesses, too quickly (slowly), automatically increases (decreases) the size of the search space for the next acceptable random number to guess, thereby increasing (decreasing) the expected number of guesses required to guess correctly – provides the coordination. Without coordination – the bitcoin orchestra conductor’s decentralized re-creation of perfectly competitive ~10-minute dances, despite relentless acceleration in human ingenuity and network computing power – a central bank protocol could make C=~0, just for themselves, stealing time.

Satoshi’s solution: a decentralized clock for decentralized timestamping of monetary transactions. Bitcoin is a clock with a new concept of time – block height – synchronously marking depletion of the most valuable resource in the universe, our time.

Universal constants – the speed of light c, gravitation G, the elementary charge e – are physical quantities, dependent on no one, measurable by anyone, and the answer never changes. They have foundational roles in our lives.

Bitcoin’s tick, the incremental block height pace, b, is the world’s new universal constant – silently, unstoppably, trustlessly ticking. Dependent on no one, measurable by anyone, the answer never changing, b now has a foundational role in our lives.

Satoshi’s b-paced clock emancipated fiat time enslavement. Humanity can finally trust the ledger, demolishing our central bank chains.

b=1

Tick tock, next block.

DO NOT SKIP PRACTICE FOR ONE DAY

What do urban rent control and voluntary employee turnover at Stone Ridge have in common?

In 1946, 35-year-old former University of Chicago Ph.D. student Milton Friedman and 36-year-old University of Chicago professor George Stigler, both future Nobel winners, co-authored the landmark essay Roofs or Ceilings? Ostensibly about rent control, their essay provided a blueprint for the kind of firm culture I aspired to have at Stone Ridge when I started the firm.

The 1906 San Francisco earthquake destroyed 3,400 acres of buildings in the heart of the city, including half the structures that housed its population of ~400,000, triggering the greatest housing challenge in US history.

Some people immediately left the city to stay with relatives nearby. For others, camps and shelters were quickly established and new construction proceeded rapidly. Yet, about one-fifth of San Francisco’s population had to fit, somehow, into the still-standing half of the housing stock, which was already occupied. This meant that each remaining house had to shelter, somehow, on average 40% more people, and fast.

Not only was there no subsequent homeless problem, the first post-quake publication of the San Francisco Chronicle, five weeks post-event, did not even mention a housing shortage. The classifieds contained 64 advertisements of houses “available for rent,” 19 “for sale,” and only five for “wanted to rent”.

Fast forward a mere 40 years, to 1946, just post-war. The San Francisco Mayor, amidst homelessness on the streets, declared housing “the most critical problem facing California.” The city was being asked to shelter just 10% more people, over time, than pre-war. Not 40% more people, overnight, than pre-quake.

Comparing the post-earthquake and post-war San Francisco housing strategies, Friedman-Stigler called the 1906 method “Price Rationing”, and the 1946 method “Rationing by Chance and Favoritism”. Scarcity always requires rationing. The method really matters.

The 1906 rationing method applied Smith’s free market philosophy. Non-coercive, it let high prices lead to skyrocketing supply, which led to low prices. The market cleared quickly, even without Airbnb. Merely weeks after the worst natural disaster in US history, before or since, everyone had roofs over their head, and at affordable prices. As noted above, the classifieds revealed about a 10 to 1 ratio of “available for rent” to “wanted to rent” ads. It turns out Smith was just as philosophically right about the butcher, the brewer, and the baker, as he was practically right about banking business models.

The situation in 1946 could not have been more different. The government acted almost as if they lost their copy of Wealth of Nations. Examination of the San Francisco Chronicle classifieds, amidst government imposed and coercive rent ceilings, reveals that the ratio of advertisements “seeking to rent” to those “available for rent” – the reverse order of above – was 38 to 1. Worse, the 1946 rationing method – Friedman-Stigler’s aptly named “Chance and Favoritism” – undermined civility and citizenship. Consider the prioritization of available housing.

First: to those willing to remain in the same dwelling (undermine mobility)

Second: to those willing to pay landlords cash under the table (undermine the rule of law)

Third: to friends or relatives of landlords (undermine landlord incentive for dwelling improvement)

Fourth: to the most productive, and law abiding, members of society (undermine the group working hard to support their family, without time to look for the legally-available-and-affordable-to-them-needle amidst the San Francisco housing haystack).

In a Smith-inspired warning, also tragically unheeded, Friedman-Stigler wrote, in 1946:

“The implications of rent ceilings for new construction are ominous. As long as the shortage created by rent ceilings remains, there will be clamor for continued rent controls. The shortage of dwellings perpetuates itself, with the progeny even less attractive than the parent.”

Fortunately, Stone Ridge began 66 years post-Roofs and Ceilings.

“In this country, we combine the talents and experiences of such a diverse population that we will often surprise one another.”

— Hester Peirce (2019), SEC Commissioner, Baby on Board

In designing the Stone Ridge recruiting, retention, and promotion philosophy, I considered rationing by price talent, the 1906 method, or rationing by chance and favoritism group identity, the 1946 method. The 1946 method was in vogue, and I faced enormous pressure to choose it. However, given my foundational view that people are awesome, I went with the 1906 method.

Like the classifieds above, our employee data tell a clean empirical story. Over the last two years, four people voluntarily left Stone Ridge. Two went back to school, one left for medical reasons, and one left to go to another firm.

At Stone Ridge, we do not make financial forecasts – I think they become ceilings – nor do we have KPIs, except one for me: voluntary employee turnover. If it is not under 1%, I had a bad year.

Imagine you want to be around insatiably curious and insanely smart colleagues, spend your days working on hard and important problems, and report to a manager, and a CEO, who each know you and want your career to soar. You know it cannot be all roses every day, but you have heard that when the firm goes through periodic significant challenges, all colleagues lock arms together, and finger pointing is prohibited. Oh, and imagine you generally get paid pretty well (though totally up to you whether you convert it into bitcoin).

I am not aware of anywhere besides Stone Ridge you get to analyze Ruscha for breakfast, calculate expected profit of bitcoin mining pools for lunch, start a new SFR asset management company for dinner.

HELP WANTED: Join a startup with others committed to share, dream, and build. Prerequisites: childlike sense of wonder, five days/week in the office. Many meals eaten together, sample projects below. Assume luck favors those having a great time together.

Ruscha for breakfast: measure market depth in his last 250 auctions, as a potential input into the maximum loan-to-value (LTV) constraint in our forthcoming art lending business (cue trying to make money in art: take two).

Bitcoin mining pools for lunch: evaluate the impact of the pools ignoring the least, and most, valuable three blocks per day, to determine the true cost of not self-mining (cue NYDIG self-mining: take one).

SFR asset management company for dinner: based on our observations about the history of bank runs, an Adam Smith-inspired view of the most ethical long-term owners of SFR, and our CEO’s anaphylactic aversion to bailouts, launch a firm comprised only of investors with “forever balance sheets” (stay tuned).

No one has just one job at Stone Ridge, and no one wants one. Instead, we have an explicit “majors” and “minors” system (and even some double majors and some double minors). School is more interesting that way.

“I’m going to speak my mind, so this won’t take very long.”

— Banksy

Firmwide communication at Stone Ridge is in the oral tradition. I have not written a memo since firm inception. Somehow everyone knows how to behave. Our culture, distinguished by a civil war of kindness pitting colleague against colleague, elevates the smallest minority on earth, the one worthy of protection and special treatment: the individual.

At Stone Ridge, discrimination on the basis of anything other than merit is strictly forbidden. We do not measure, and I do not care about, the percentage of any employee group identity. As a matter of practice, we do not keep lists of irrelevancies. Not having HR means never having to play pretend games with pretend data with pretend motives. If you work at Stone Ridge, it is because you are awesome. 1906-style, we do not need HR, or the government, to tell us that rationing talent by talent is the right way to manage Stone Ridge, and the only chance I have of hitting my annual KPI.

That last constraint has cost us (many) billions of dollars of AUM. Since before our firm had an office, employees, or assets – when it was just me alone in my apartment cold-calling – I answered employee demographic questions on investor DDQs with “N/A.” I decided that if the answer needed to be different for me to have a firm, I would not have one. We still regularly get those questions, and I still want to ace my exams. N/A is our answer. It is the only one that gets full credit.

“A wall has always been the best place to publish your work.”

— Banksy

I invite you to visit our office in 2025. Our office is such a special place to us. It is our dojo. It is where we go to train. There is no dust in the corners. We practice reinsurance and lending and bitcoin, yes, but our deepest practice is seeking mastery of compassion towards each other, in witness to our repeated, mostly unsuccessful, attempts at breakthrough creativity. Unafraid to publish our work on the wall, we try again. And again. And again. I have yet to find the upper limit of my awe of the talent, fearlessness, and determination of my colleagues.

Our progress at Stone Ridge has not been, and will not be, a straight line up and to the right. We have not been, and will not be, immune to known unknowns and unknown unknowns causing significant and unexpected loss. On your visit, however, I am positive you will feel the ascendant energy of our space.

In hindsight, I realize I have been holding us back by too timidly placing the bar on our potential as a firm. I now know I do us a disservice by placing it anywhere.

OUR PARTNERSHIP

As we enter 2025, our tanks are filled with energy, gratitude, and inspiration. We innovate to prepare for an uncertain future, in pursuit of our mission: financial security for all.

Stone Ridge is most proud of the partnership we have with you, our investors. We are on the path together. You contribute the capital to propel and sustain groundbreaking product development. We contribute our collective career’s worth of experience in sourcing, structuring, execution, and risk management. Together, it works. In that spirit, I offer my deepest gratitude to you for sharing responsibility for your wealth with us this year. We look forward to serving you again in 2025.

Warmly,

Ross L. Stevens

Founder, CEO

iPerhaps the best way to explain exactly how this part works is via reference to Season 2, episode 17 of South Park, in which the gnomes explain that their business has three distinct components, each critical to success. Phase 1: Collect underpants, Phase 2: ?, Phase 3: Profit. This part is Phase 2.

iiTo our knowledge, this was the largest (by over 2x) and most subscribed natural gas PDP ABS issuance in the industry.

iiiAt Stone Ridge, if you give advice and someone follows it, you must be exposed to the consequences. Our code is symmetry with our investors, having a share of the harm and paying a material financial penalty if something goes wrong, regardless of the cause. Taking the equity tranches, and necessarily bearing the first loss risk, in our own securitizations represents the ideal embodiment of this ethos.

ivThis section is inspired by The Dead Pledge, by Judge Earl Glock, select concepts and phrases from the book.

vHannover Re, Munich Re, and Swiss Re (largest by balance sheet size): average annualized ROA from Jan 2020 (Longtail Re inception) to Sep 2024 (latest available) of 2.2%. Longtail Re ROA as of Nov 2024.

viAverage annualized ROE over equivalent period of 4.7%. Return on Equity is a non-GAAP financial measure, calculated as the percent change in book value per share, adjusted for any dividends paid. Source: Bloomberg.

viiIn a radical departure from precedent and mandate, the Federal Reserve began buying mortgage-backed securities (MBS) in October 2012. The largest financial actor in the economy, with unlimited fiat resources, price insensitively – via mechanical monthly MBS purchase programs using printed pieces of unbacked paper – buying MBS themselves is directionally equivalent to that actor price insensitively buying individual houses. At the time of the Fed’s shocking MBS decision, Richmond Fed President Lacker wrote, in a seething dissent, “I strongly oppose purchasing MBS. Purchasing MBS can be expected to reduce borrowing rates for home mortgages by more than the borrowing rates for small business, autos, or unsecured consumer loans. Deliberately tilting the flow of credit to one economic sector is an inappropriate role for the Federal Reserve. Government decisions to influence the allocation of credit are the province of fiscal authorities.” In the ensuing 12-year period to today, the Case-Shiller US National House Price Index increased 7%/year. In the symmetrically chosen previous 12 years prior to the Fed’s shocking MBS decision, that index rose 2%/year. The Fed’s MBS decision – today it owns more than $2 trillion of MBS – has made US housing unaffordable to virtually all Americans that did not already own houses prior to 2012. Due to the power of compounding, Fed-created US home ownership apartheid gets worse with time. Not surprisingly, the State duplicitously attempts to shift the blame for high US house prices to institutional home buyers, the very actors solving the problem for American families. “Potential home buyers are unable to compete with large investors and their seemingly limitless cash on hand,” said Senator Elizabeth Warren in 2022, expressing typical State sentiment. Warren should know better. In reality, the Fed is the only housing investor with limitless cash. “There is an infinite amount of cash in the Federal Reserve,” said Minneapolis Fed President Neel Kashkari in March 2020, immediately after which the National House price index began rising over 10%/year. In sharp contrast, institutional home buyers, fiduciaries with a profit motive, are the most hyper-price-sensitive buyers. An institution will never bid up a house because they like it. They will never live in it. A family will always be the marginal buyer. They can amortize the purchase price over a far longer expected ownership period and, appropriately, value a safe neighborhood and good school district, and a particularly unique home they love, marginally above any institution. In the Stone Ridge SFR business, with our main partner, we are the highest bidder in only 4% of the houses we seek to purchase. Overall, institutions own ~0.5% of all US single-family houses. Under today’s price-distorted market conditions, the more homes institutions own the better for American families. For every one family that can afford to buy their first typical America home, there are five families that cannot, but can afford to rent one. Institutions did not create the affordability crisis – the Fed did – but through their SFR programs, institutional investors, including Stone Ridge, are the only ones doing anything about it. Stone Ridge is proud to help make access to outstanding homes possible for American families, and provide them with world-class tenant services.

viiiAlex Gladstein introduced this concept at the 2024 Stone Ridge CEO/CIO Conference.

ixTaleb, Nassim Nicholas, Antifragile: Things That Gain from Disorder.

xNakomoto, Satoshi, “Bitcoin open source implementation of P2P currency”, February 11, 2009. Available at https://satoshi.nakamotoinstitute. org/posts/p2pfoundation/1/. Accessed December 27, 2024.

xiGigi’s incomparable, groundbreaking Bitcoin is Time introduced me to the ideas in this section, select concepts and phrases used with permission of the author.

Standardized returns as of most recent quarter-end (9/30/2024)

Results reflect the reinvestment of dividends and other earnings and are net of fees and expenses where applicable. Performance data quoted represents past performance; past performance does not guarantee future results.

Standardized returns as of most recent month-end (11/30/2024)

Risk Disclosures

This communication has been prepared solely for informational purposes and does not represent investment advice or provide an opinion regarding the fairness of any transaction to any and all parties nor does it constitute an offer, solicitation or a recommendation to buy or sell any particular security or instrument or to adopt any investment strategy. Charts and graphs provided herein are for illustrative purposes only. This communication is not research and should not be treated as research. This communication does not represent valuation judgments with respect to any financial instrument, issuer, security or sector that may be described or referenced herein and does not represent a formal or official view of Stone Ridge.

It should not be assumed that Stone Ridge will make investment recommendations in the future that are consistent with the views expressed herein, or use any or all of the techniques or methods of analysis described herein in managing client accounts. Stone Ridge and its affiliates may have positions (long or short) or engage in securities transactions that are not consistent with the information and views expressed in this communication.

There can be no assurance that any investment strategy or technique will be successful. Historic market trends are not reliable indicators of actual future market behavior or future performance of any particular investment, which may differ materially, and should not be relied upon as such. Target or recommended allocations contained herein are subject to change. There is no assurance that such allocations will produce the desired results. The investment strategies, techniques or philosophies discussed herein may be unsuitable for investors depending on their specific investment objectives and financial situation.

The information provided herein is valid only for the purpose stated herein and as of the date hereof (or such other date as may be indicated herein) and no undertaking has been made to update the information, which may be superseded by subsequent market events or for other reasons. The information in this communication may contain projections or other forward-looking statements regarding future events, targets, forecasts or expectations regarding the strategies, techniques or investment philosophies described herein. Stone Ridge neither assumes any duty to nor undertakes to update any forward-looking statements. There is no assurance that any forward-looking events or targets will be achieved, and actual outcomes may be significantly different from those shown herein.

Information furnished by others, upon which all or portions of this communication are based, are from sources believed to be reliable. However, Stone Ridge makes no representation as to the accuracy, adequacy or completeness of such information and has accepted the information without further verification. No warranty is given as to the accuracy, adequacy or completeness of such information. No responsibility is taken for changes in market conditions or laws or regulations and no obligation is assumed to revise this communication to reflect changes, events or conditions that occur subsequent to the date hereof.

Nothing contained herein constitutes investment, legal, tax or other advice nor is it to be relied on in making an investment or other decision. Legal advice can only be provided by legal counsel. Before deciding to proceed with any investment, investors should review all relevant investment considerations and consult with their own advisors. Any decision to invest should be made solely in reliance upon the definitive offering documents for the investment. Stone Ridge shall have no liability to any third party in respect of this communication or any actions taken or decisions made as a consequence of the information set forth herein. By accepting this communication, the recipient acknowledges its understanding and acceptance of the foregoing terms.